十九世紀,流行一種休息療法蔚為風潮。如果你是女生,用腦過多,能量感到枯竭耗盡,去看醫生,醫生開的處方會是…要你躺平,躺平至少六到八個禮拜;中間除了上廁所(應該包含洗澡)以外,嚴禁做任何其他的事,讀小說也不行。就是躺平,以及喝牛奶,很多牛奶;有時是醫護人員在旁服侍。XD

男生的處方則是….對!男女處方不同。會是去西部當牛仔,砍砍柴,生營火,烤BarBQ。

案例中的C女士,經過這樣的調理,臉頰豐腴,增重20公斤。因緊張而消失的經期又重新回來。這是醫生感到很滿意的成功案例,足以證明脂肪,血液和活力,這三個重點全回到正常狀態。

兩百年後的現在看來,雖覺得有點荒誕好笑,但仔細想想不無道理。

十九世紀正是火車/電報啟用,快速進入商業化的開始。發明與倡導『休息療法』的這位醫生米歇爾當時就問:

『我們的生活步調是否太快?』(他如果知道後人加速過日子,不知做何感想?)

也提醒人們在進行『殘忍的金錢競賽』。(他也不知道後人玩多大)?

現在走過千山萬水,感覺我們又走回原點。可不是嗎,休息是為了走更長的路。

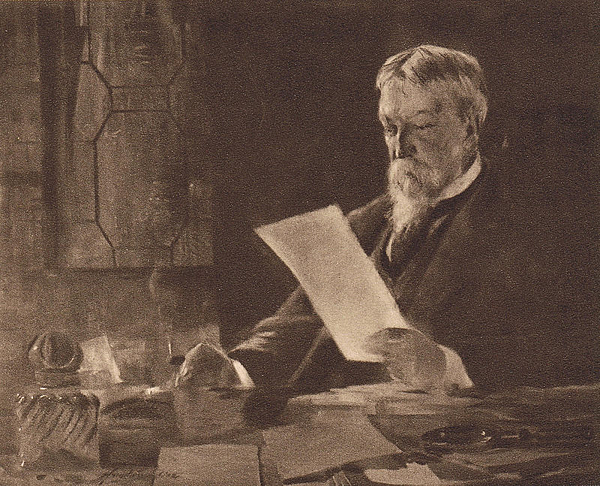

(喔,對了。不是所有人都有這奢侈可以躺平六到八星期,有人要工作養家,哪經得起。所以這是當時有錢人的醫療風潮,窮人沒有關進收容所就不錯。這又是後話。) 附圖則生動描繪了當時的醫療風氣

『美國神經學之父』開立給婦女的處方,

是幾個月不動只喝牛奶

維吉妮亞伍爾夫以及夏綠蒂

都是他不名譽休息療法的患者

作者: 艾比

一個月以來,“C女士“躺在床上,喝下幾公升的牛奶。除了偶爾坐起來或上廁所,這位33歲的新英格蘭女士需要躺平。她被認為是生病或至少是“疲憊不堪”。但根據-席拉斯.維爾.米契爾醫生的說法,他嚴格的『休息療法』讓她得到改善。到月底,她體重增加40磅(約18公斤),並成為他最成功的案例之一。

米契爾開創的休息療法,在19世紀後期出人意外地大受歡迎,幾位醫生採用並實踐了數十年。直到後來它寫進教科書,是美國醫學進步相當擾人的跳脫式療法,這種形同詐騙的療法,可以與嚴謹的醫學創新並行。

在19世紀,精神病學的執業迅速發展,賓州的神經學家米契爾站在最前端。 南北內戰給年輕的醫生創造機會能在戰場一試身手,特別是精神病學家,能夠處理戰時的創傷,以及神經系統受傷的手術。新型步槍與扁平子彈被稱為『迷你球』,會穿透骨頭撕裂組織,讓士兵受到毀滅性傷害需要快速截肢。幾分鐘內就失去手臂與腿,戰爭結束時,成千上萬的肢體被截肢。

米契爾身為一名年輕的外科醫生,在戰場上找到他的位置,在費城專業的領域工作。他很快對於當時還不是很被人了解的截肢者的『神經損傷』產生興趣,這些截肢者在被截肢的部位,會經歷莫名的幽靈般的疼痛。米契爾在這個主題寫了大量的文章,把這現象稱為『幻肢痛』。作為在新興的醫學領域迅速竄起的醫生,他贏得『現代美國神經學之父』的稱號。

但米契爾對於『神經損傷』的興趣開始超越戰場。戰爭結束後,他越來越關注於在科技進步下的美國,其神經與生物的效應。

『我們的生活步調是否太快』,在他1871年的著作『疲累磨損』當中這樣問。『殘忍的金錢競賽』,伴隨『電報鐵路的競賽速度』進入商業生活』。在社會以及人體埋下了某些陰沉的東西。

他相信,美國的進步不是沒有神經方面的後果的。城市精英一定失去了某些東西,他們處於快速變化與急速火車當中。他認為,現代化可能消耗掉有限的『緊張能量』,使身體與心智掏空生病。當人們過度思考,唯一恢復正常的方法就是休息。

根據神經科醫生的說法,患有『神經衰弱症』的人,這是米契爾發明的術語,顯示出當代會有的毛病。從頭痛、嗜睡,體重減輕到性功能障礙的症狀。對於男人來說,解藥就是:去西部砍柴,營地升火煮牛肉。某種程度,這是19世紀專業開出的類似處方旅行到牧場。

但治療對女生來說,不是那麼簡單。女生也發現自己受到現代生活節奏的影響,或至少在醫療趨勢上被掃到。更具體地說,白人,上層階級,受過良好教育的女性,形成米契爾的病者的結構。享有特權地位的女性,像是作家和藝術家,在家庭以外的機會變多。但米契爾認為,如此廣泛運用心智,很容易耗盡他們的能量炸掉他們脆弱的神經。

米契爾為這些女性開出的治療處方,『神經質的女性』,米契爾寫道,『通常,很瘦,貧血。』以及平息過度亢奮的大腦以及血液供應不足的方法,基本上就是開給她一個長長的,有牛奶補充的,非常必需的休息。

根據作者與歷史學家珍妮佛蘭貝博士的說法,一些女生因為一些症狀去找米契爾。通常她們看來很像當時很多精神科醫生會說的『歇斯底里症』的顯現,混和了心理緊張與身體的緊張。一些患者會有焦慮,疲勞,甚至失明。有些則完全不再說話。

雖然根據每位患者的症狀和嚴重程度量身打造療法,但治療通常還是要六到八個禮拜,絕對的臥床休息。患者通常完全與世隔離,偶爾與護士進行互動。『我會把它形容成冬眠,』蘭貝說。『結合冬眠前期,比方,熊必須事先吃很多東西。』

在治療的第一階段,米契爾通常完全禁止他的病人起來,除了坐起來被餵食或起來上廁所。但一些特別極端的狀況,米切爾寫道,休息可能會持續數個月。 一旦允許可以更常坐起來時,仍是禁止閱讀,寫作,繪畫或做任何用到頭腦的活動。

但臥床休息只是治療的一個面向。米契爾開的處方,還有經常的『按摩』以刺激肌肉才不會有疲累感。然而,這些都蠻激烈的,不太像在放鬆。米契爾寫道:

『整個肚子被手部快速的動作搖撼。』

『有時候手平平或拱起來拍打』。『

『按摩有時補充電流通過腿部肌肉,腹部,背部和腰部,顯然是為了刺激肌肉』提供他所說的『無痛運動』。

也許治療最奇怪的部分是嚴格的過度餵食,非常偏頗在牛奶。米契爾寫道,治療不能沒有乳製品。頭幾天專門給予休息患者,後來補充高脂肪,高熱量的膳食。米契爾建議,隨著個案的進展,牛奶可能換成各種『兒童食品』,像是麥芽牛奶或『雀巢食品』。

對於這種像嬰兒待在子宮式的治療,有一些令人不安的事。他寫道,過度飲用牛奶會很想睡覺,而且『舌頭會有層白白的東西,隔天早上留有一層不舒服的甜味......這兩種可以不用太在意。』

過量飲用牛奶會很極度想睡覺。

米契爾對於他所寫文章“脂肪與血液”的成功表示滿意。C女士臉部豐腴起來,多年沒有的經期恢復,足以對神經科醫生證明脂肪,血液和活力已然恢復。很快,其他醫生採行這樣的療法,似乎鼓勵了米契爾,或至少讓他免除全部的責任。 『我很幸運能顯示,除了我自己之外,這項療法完全證明他自己,不需要原作者的辯護或道歉。』

但是,在書的最後,有一絲絲的自我覺悟。也許醫生直覺到他的行為引起爭議。『我現在更擔心它會被濫用,或用在不需要之處,而不是擔心它沒用被用,』他寫道,『還有謹慎地說,我再次留給時間與我的職業來判斷。』

隨著時間的推移,責難時有所聞。夏綠地(Charlotte Perkins Gilman),作家也是米契爾的病人,寫了一篇黃色壁紙的虛構故事,其實有關她在接受治療的經歷。不令人意外地,主角被弄到發瘋。維吉妮亞伍爾夫也被她的婦科醫生(米歇爾的同時間的人)治療,也是認真寫了不滿的文章。

很容易將此描述為系統性,父權壓制的情況。但蘭貝指出,還有一個更複雜的動態在運轉。看來並非女性總是不由自主走進病人的位置。蘭貝說,身為先進社會的一分子,經常為此感到惋惜。換句話說,在體驗技術與現代生活的不適中有一絲絲的優越感,因為這能反映她的特權與地位。

接受米契爾治療的女性,屬於當時的菁英份子(上流社會)負擔得起,並哀嘆科技與社會的進步。雖然很奇怪令人感到窒息,但又有點時髦。蘭貝指出,有更多女性,通常是移民或貧窮人家,永遠負擔不起這種私人客製化診療。取而代之的,這些婦女通常進了公共收容所,或完全沒辦法得到治療,她們的痛苦以及美國精神病學史上的一部分,都不見光(都不為世人所了解)。

直到20世紀,用於女性的全面診斷才開始下降。在第二次世界大戰之前,臥床休息直到二戰才被揭露沒什麼效果,當時醫生注意到長時間休息,對於幫助士兵恢復,並不是特別有效。不久之後,研究顯示臥床不動,實際上,對身體有害,對每個主要器官也會有負面影響。最終,治療首重休息的方式,在神經學的進化是黑暗的曇花一現,科學和偽科學警告說,美國神經學之父與其他治療方法的發明者,可以彼此不衝突。

但蘭貝認為,治療背後的核心理念,至今看來並沒有離很遠。「你可以在今天的健康文化中找到類似的東西。」她說,「比方遠離,將自己抽離惱人的一切,遵循特殊嚴格的飲食,重新出發。」

畢竟誰不渴望放慢一直在加快的工作步,調以及不可避免的社交聊天。過度工作,過度刺激,我們都知道要休息,找安靜的地方,修復身體。有充分的睡眠。如果外在世界無法放慢腳步,至少我們可以為自己而做。就攤坐在沙發(也許來點冰淇淋,自己挖來吃) 。轉到電影台,關掉心智的吵雜。

The ‘Father of American Neurology’ Prescribed Women Months of Motionless Milk-Drinking

Virginia Woolf and Charlotte Perkins Gilman were both patients of his infamous rest cure.

by Abbey Perreault

September 28, 2018

For over a month, “Mrs. C” laid in bed, gulping down quarts of milk. Aside from occasionally sitting up and relieving herself, the 33-year-old New Englander remained horizontal. She had been deemed sick, or “wearied” at the least. But according to Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, his strict “rest cure” regimen had her on the mend. By the end of the month, she’d gained 40 pounds and a spot among his most successful cases.

The rest cure that Mitchell pioneered rose to surprising popularity in the late 1800s, and several physicians adopted and practiced the treatment for decades. Only later did it become a textbook example of the disturbing nonlinearity of American medical progress, the quackery that can live alongside rigorous medical innovation.

In the 19th century, the practice of psychiatry was rapidly evolving, and Mitchell, a neurologist from Pennsylvania, was at its forefront. The Civil War created a fresh need for young physicians willing to cut their teeth on the battlefield, particularly psychiatrists able to work with wartime trauma and surgeons treating injuries of the nervous system. New front-loading rifles and flattening bullets called “minnie balls” burst through bone and tore across tissue, leaving soldiers with devastating wounds treated by rapid amputation. Arms and legs were removed in mere minutes, and by the war’s end, tens of thousands of limbs had been amputated.

Mitchell found his place on the battlefield as a young surgeon, working at a specialty ward in Philadelphia. He quickly took an interest in the not-yet-understood “nerve injuries” of amputees who experienced inexplicable, ghostly pain lingering where an arm or leg had once been. Mitchell wrote extensively on the subject, and coined the phenomenon “phantom limb syndrome.” As a quickly ascending physician in the fledgling field, he was awarded the title “Father of Modern American Neurology.”

But Mitchell’s interest in “nerve injuries” began to branch beyond the battlefield. After the war, he became increasingly concerned with the neurological and biological effects of a technologically advancing America. “Have we lived too fast?” he asks in his 1871 book, Wear and Tear. The “cruel competition for the dollar,” he posits, along with the “racing speed which the telegraph and railway … introduced into commercial life” had planted something insidious in society, as well as within the human body.

American progress, he believed, was not without its neurological consequences. Something must be amiss among the urban elite, who were at the crux of rapid change and hurtling trains. Modernity, he posited, could deplete finite stores of “nervous energy,” leaving bodies and minds exhausted and sick. And when people overexert their minds, the only way to return to normalcy was to rest.

According to the neurologist, a person sick with “neurasthenia,” a term coined by a contemporary of Mitchell’s, might show symptoms ranging from headaches to lethargy, or weight loss to impotence. For men, the antidote was simple: Go West, chop some wood, maybe even cook some mannish meat over a rip-roaring fire. In a way, it was the 19th-century, professionally-prescribed analogue to a trip to the dude ranch.

But the cure was not quite so simple for women. Ladies, too, found themselves impaired by the pace of modern life, or, at least, swept up in the medical trend. More specifically, white, upper-class, educated women came to dominate Mitchell’s patient demographic. Women who occupied privileged positions like this, who were often writers and artists, had been increasingly afforded time outside of the home, the opportunity to socialize, and higher education. But using their minds so extensively, Mitchell believed, could easily deplete their energy and fry their fragile nerves.

Mitchell proceeded to prescribe the rest cure almost exclusively to these women—“nervous women,” writes Mitchell, “who, as a rule, are thin and lack blood.” And the way to quell the overexerted brain and depleted blood supply of a woman was to, essentially, prescribe her a long, milky, much-needed rest.

According to author and historian Dr. Jennifer Lambe, a number of symptoms brought women to Mitchell. Often, they looked like what many psychiatrists at the time would call manifestations of “hysteria,” an intense mixing of the psychological and the somatic. Some patients complained of anxiety, fatigue, and even blindness. Others had stopped speaking entirely.

Though customized to cater to each patient’s symptoms and severity, the treatment typically entailed six to eight weeks of absolute bed rest. Patients were most often placed in complete isolation, interacting only occasionally with a nurse. “I would describe it as a kind of hibernation,” says Lambe. “Combined with the pre-hibernation period, when, for instance, a bear has to eat a lot beforehand.”

During the first phase of the cure, Mitchell typically forbade his patients to rise at all, with the exception of sitting up for spoon-feeding or getting up to relieve themselves. But when dealing with particularly extreme cases, Mitchell writes, this period of total repose could be stretched to months. Once they were allowed to sit up more frequently, however, reading, writing, drawing, or doing anything that might require using the mind remained forbidden.

But bed rest was only one aspect of the treatment. Mitchell prescribed his patients frequent “massages” to stimulate the muscles without exhausting them. These, however, were incredibly vigorous and were likely far from relaxing. “The whole belly is shaken by a rapid vibratory motion of the hands,” writes Mitchell, “to which is sometimes added succussion by slapping with the flat or cupped hand.” Massage could be supplemented with the passage of an electric current through the leg muscles, belly, back, and loins, apparently to stimulate muscles and provide what he referred to as “painless exercise.”

Perhaps the strangest aspect of the treatment was its strict overfeeding regimen, which was heavily reliant upon milk. Mitchell writes that it was nearly impossible to treat any case without the dairy product. It was often doled out exclusively to the resting patient for the first few days, and later supplemented with high-fat, highly caloric meals. As the case progressed, Mitchell suggested, milk might be swapped out for various “children’s foods,” such as malted milk or “Nestle’s food.”

There’s something deeply disturbing about this infantilizing, womb-like treatment. The milk, consumed in excess, gave rise to extreme sleepiness, he writes, as well as “a white and thick fur on the tongue, and often for a time an unpleasant sweetish taste in the early morning … neither of which need be regarded.”

The milk, consumed in excess, gave rise to extreme sleepiness.

Mitchell writes with apparent satisfaction about his successes in his essay, Fat and Blood. Mrs. C’s “gain in flesh about the face” and resumed menstruation after years of missing periods was evidence enough for the neurologist that fat, blood, and vitality had been restored. Soon, other physicians adopted the practice, which seemingly encouraged Mitchell, or at least allowed him to absolve himself of full accountability. “I am fortunate now in having been able to show that in other hands than my own, this treatment has so thoroughly justified itself as to need no further defence or apology from its author.”

But there’s a glimmer of self-awareness in the book’s final, somewhat ominous, conclusions. Perhaps the physician intuited that his actions would be controversial. “I am now more fearful that it will be misused, or used where it is not needed, than that it will not be used,” he writes, “and, with this word of caution, I leave it again to the judgment of time and my profession.”

With time, condemnation arrived. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author and patient of Mitchell, wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, a fictionalized account of her experience undergoing treatment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the main character is driven to madness. Virginia Woolf, too, was prescribed the rest cure by her gynecologist, one of Mitchell’s British contemporaries, and wrote passionately against the practice.

It would be easy to describe this as yet another case of systemic, patriarchal oppression. But Lambe points out that there was also a more complex dynamic at play. Women, it seems, weren’t always entering the position of patient involuntarily. Being part of an advancing society, suggests Lambe, often begets a bemoaning of it. In other words, there’s a glimmer of pride in experiencing the afflictions associated with technology and modern life, because it also reflects privilege and status.

The women who were treated by Mitchell’s cure belonged to an elite group that could afford to engage with, and bemoan, technological and social progress. While it was strange and suffocating, it was also likely somewhat stylish. Lambe points out that there were countless women, often immigrants or from poor populations, who could never have afforded private psychiatric care. Instead, these women often ended up in public asylums, or received no care at all, and their suffering and part in the history of American psychiatry stayed out of sight.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the catch-all diagnoses applied to women began to decline. Bed rest wasn’t fully debunked until World War II, when physicians noticed that extended periods of repose weren’t incredibly effective in helping soldiers recover. Soon after, studies revealed that immobilization was, in fact, harmful to the body, negatively affecting every major organ system. Eventually, the rest cure was put to rest, a dark blip on the evolution of neurology, and a warning that science and pseudoscience, the Father of American Neurology and the inventor of the rest cure, can coincide.

But the core idea behind the cure, Lambe suggests, is not so far behind us. “You can find analogues in today’s wellness culture,” she says, “such as the retreat, where you remove yourself from all the things that are ailing you, eat a very specific, austere diet, and reboot.”

Who, after all, hasn’t itched to ditch the ever-increasing pace of work and inescapable chatter of social media? Overworked and overstimulated, we’re told to take breaks, seek out quiet spaces, replenish the body, and get enough sleep. If the world outside can’t slow down for us, we can do it ourselves, by reclining on the couch (perhaps spoon-feeding ourselves a pint of ice cream), turning on Netflix, and turning off the mind.

留言列表

留言列表